The prestigious blue-riband championship events were virtually monopolized in 1958, 1959 and 1960 by John Surtees on the metronomic MV, while his erstwhile Gilera adversaries campaigned such second-rate steeds as were available. Duke, after a demoralizing spell on BMW twins, retired from the sport which he had graced for a decade, McIntyre reverted to Joe Potts-prepared singles and Liberati opted for a trusty Saturno. At the close of the 1960 season, Gilera’s general manager, Michele Bianchi, revealed that the parsimonious company had postponed its much-awaited return to the tracks.

The anouncement prompted Stan Hailwood into immediate action. He flew to Milan in November and turned up at Arcore brandishing an open cheque, offering to buy the entire race shop. When this extravagant offer was rejected, he attempted to procure the use of two of the priceless multis for Mike and Bob McIntyre for the 1961 season. This effort was also doomed to, and duly met with, failure. By 1962, Commendatore Gilera’s long- suppressed enthusiasm had been rekindled, as he was constantly pestered by the likes of Liberati and Milani. Works participation seemed im minent when, in March 1962, fate dealt a harsh blow. Libero Liberati habitually practised over local roads around Terni on his private road going Saturno. On one such outing, he skidded on the exposed rails of a level crossing that had been made slippery by a shower of rain. He hit a wall and died shortly afterwards. Gilera’s hopes now rested with McIntyre but, despairing of extracting a decision from the dithering poten tates in Arcore, he had signed for the burgeoning Honda empire.

Tragically, the universally admired Scot sustained fatal injuries in an Oulton Park crash in August. The Remembrance meeting at the same circuit some weeks later featured demonstration laps by a cluster of celebrities, including Duke aboard a dustbin-faired Gilera. Ironically, this was to be the prelude to the marque’s competitive renaissance. John Hartle rode the multi at Oulton prior to the meeting and it was entrusted to Derek Minter for a tyre-testing session at Mallory Park, where he came within a second of the lap record.

This was the opening Duke had been impatiently waiting for; he now obtained machines for a romp at Monza early in 1963 to assess prospects. Minter was the obvious choice to put the dust laden bike through its paces. He had been at the peak of his form in 1962 when he had pointedly ignored Honda team orders to ride to a splendid 250 cc TT victory on a tired Hondis Ltd-entered 1961 model. The second string was Hartle, who boasted experience of a fearsome multi from his days as an Agusta runner. Enzo Ferrari had masterminded a motorcycle racing team in pre-war days. He formed a friendship with Giuseppe Gilera that was strengthened in later years when they shared the grief of losing an only son. Gilera had helped out the Maranello factory when the controversial 1.5 litre limit was introduced for Formula 1 in 1961. The Prancing Horse equipe now reciprocated by assisting with the preparation of 500cc and 350cc engines for the Monza tests.The new dolphin fairings were fibreglass Bill Jakeman jobs. As riding techniques had changed over the last five years, wads of foam were taped to the backrests of the seats so that the two riders could sit further forward and lean more when cornering. Severe fog and ice delayed and ultimately hampered the tests. Although the 350 cc bike was way off the Monza pace, the senior model appeared to be competitive and Commendatore Gilera willingly gave the go-ahead for a comeback, despite some misgivings in the boardroom.

The effort was essentially private. Duke’s reputation was sufficient to obtain finance from Castrol and Avon and he negotiated starting money for his riders. The factory’s contribution was restricted to the bikes and the provision of mechanics, primarily the faithful Giovanni Fumagalli and Luigi Colombo; Giuseppe Gilera was not about to unveil the engine’s secrets to prying outsiders. Ominously, some needless friction arose at this early stage in the proceedings when the factory, unbeknown to Duke, approached Hailwood for his signature, which was, however, to be appended to an Agusta contract.

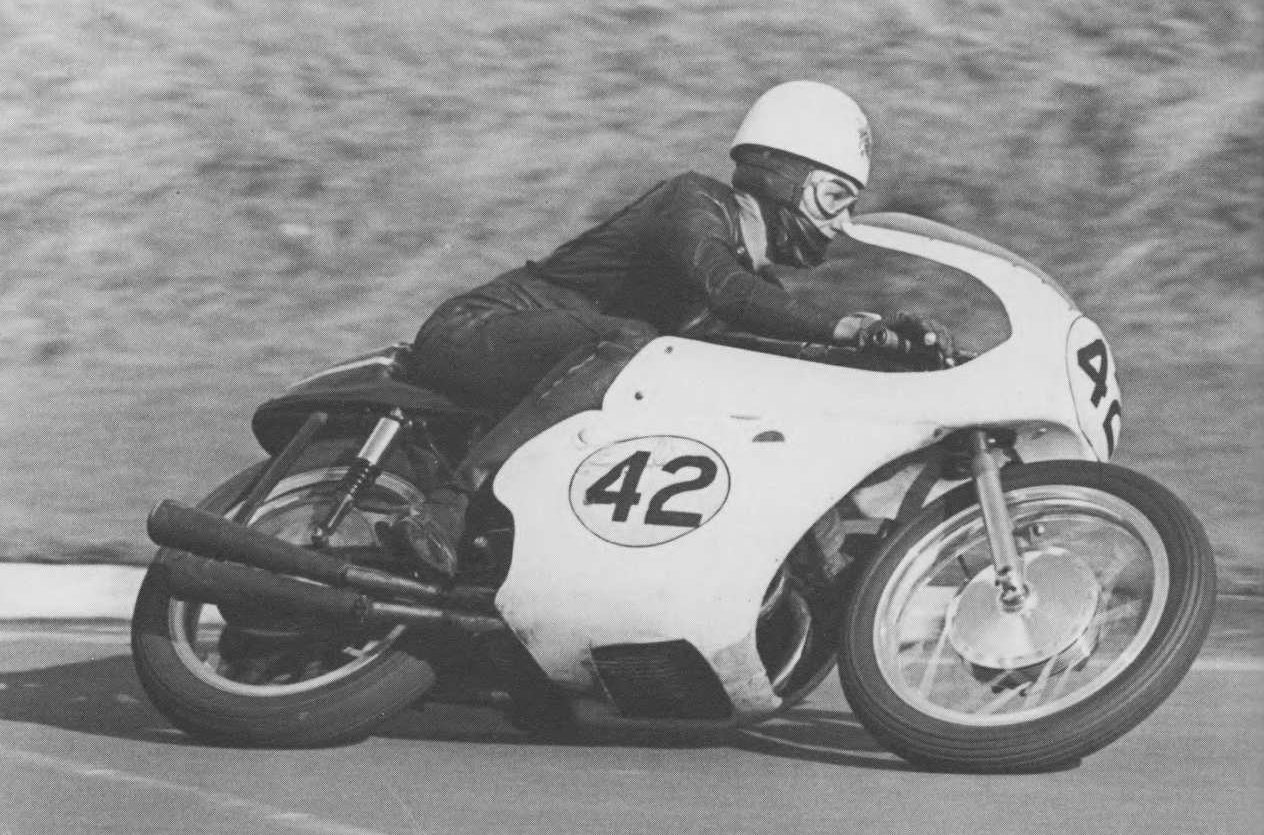

The Scuderia Duke enterprise materialized in April, when Minter rode to a handsome victory at Silverstone, although Hartle struggled to fend off the eager young Phil Read. Minter immediately sensed a problem with the front suspension, which had been strengthened years earlier to cope with the pressure created by, and indeed the weight of, the now discarded dustbin fairing. Minter suggested experimenting with the swinging-arm in order to transfer weight and was more than a little irritated when Duke chose to ignore him and test a range of shock-absorber fluids in search of an answer. Fortunately, internal dissensions were assuaged by Minter’s victories at Brands Hatch and Oulton Park before enthusiastic crowds of 60,000, anxious to savour the sight and sound of the legendary Arcore multis. Confrontation with the Gallarate squad, now restored to full-blooded works status after two seasons of notionally ‘Privat’ participation, was eagerly anticipated. The big showdown came at the Imola Gold Cup, when Minter and Hartle humbled the peerless Hailwood and his back-up rider, new recruit Silvio Grassetti. Although suffering from a troublesome wrist injury, Hailwood made no excuses, admitting that Minter’s riding had been unmatchable. The Oxford Flyer estimated that top speed and braking of the Gilera and the MV were on a par, but he thought that the former had a noticeable edge in acceleration, especially Hartle’s bike. Minter was another to observe, with some disgust, that Hartle was favoured with the faster engine. Remonstrating with Luigi Colombo was to no avail and so in the race Minter had to outbrake his team-mate consistently in order to make his point. Erroneously or otherwise, the King of Brands, who was not given to toeing a works line, now formed the fixed opinion that Duke and Hartle, as northerners of long-standing acquaintance, were deliberately isolating him, the presumptuous southerner.

Minter’s grievances were not confined to personal matters; he resented the fact that Duke paid no heed to his recommendations. After riding the 350 cc model in practice at Imola, he requested that the footrests be lifted. Both Colombo and Duke insisted that there had been no grounding in 1957 and were not over impressed by his suggestion that, with a dolphin fairing and improved tyres, cornering speeds had doubtless increased over the years. Once racing, he had to ride to the limit to overtake Remo Venturi on the bulky Bianchi and, having done so, he duly fell off when a footrest grounded! Minter was understandably aggrieved, while Hartle finished well down on the veteran Italian.

At Imola, the machines appeared in uitra-light thin magnesium-alloy fairings with sponge- padded knee rests. There were also new carburettor connections, but otherwise the bikes remained essentially in 1957 guise. Disaster befell Minter in May when he suffered broken vertebrae in the infamous crash at Brands Hatch that killed Dave Downer.

With the championship series beckoning, Duke hastily sought a suitable replacement and found him in Phil Read, Senior Manx GP winner in 1960 and Junior TT victor a year later. The reconstituted team’s title challenge commenced with the 350 cc race at Hockenheim. Hartle soon retired with vibration problems, leaving Read trailing in the wake of Redman’s Honda and Venturi. Technically, the 350 cc class had moved on of late, particularly with the entry of the four-valve Hondas, and the Gilera was rendered practically obsolete. Read recalls the bike with a combination of pity and horror: ‘It was irritating enough being left behind by the leaders, but eventually Tommy Robb on his 305 cc Honda twin steamed by on the straight; the bikes should have been pensioned off immediately.’ Read’s third place ahead of Havel’s Jawa was indicative of the machine’s limited capabilities.

Three 350 cc bikes were taken across the Irish Sea for the Junior TT. One engine blew up in practice and Read’s gave up the ghost on the second lap of the race. Hartle soldiered on gamely and inherited a remote second place behind the Rhodesian champion when Hailwood’s MV expired. Despite losing a cylinder when the incessant rain took its toll on the last lap, he clung on to the six championship points. Hailwood mounted a formidable challenge for the Senior TT, pointedly completing every practice lap at over the magic 100 mph. Hartle’s impressive opening tour at 105.5 mph was of no avail, for he was caught on the roads by his rival, who turned in a blistering record-breaking 106.3 mph circuit.

Mike the Bike eventually won the Trophy, a minute ahead of the Gilera team leader. Hartle’s first lap had been considerably faster than McIntyre’s best speed in 1957, but it should be remembered that Hartle had been scratching, riding into the gutters and banks on a couple of occasions as he struggled to fend off the rampant Hailwood. The relatively inexperienced Read admitted to being plain scared by the novelty of riding an unmanageable bike over the unforgiving Mountain course, yet despite suffering a malfunctioning cylinder, he averaged over 100 mph to collect a fine third place.

Scuderia Duke’s fortunes revived at the Dutch TT, where, having ditched the 350 cc project, five 500cc bikes were available. Hailwood’s MV spluttered on to two cylinders shortly after the start, enabling Hartle and Read to register an unchallenged one-two. By the time of the Belgian GP at Spa, Read was questioning the wisdom of his elevation to much-vaunted works status. He was undoubtedly impressed with the potent engine and explains:

‘There was no sudden rush as I had expected but instead there was usable power, and lots of it, from 8000 rpm. The problem, of course, was with the handling, which was too light at the front end. Not much pressure could be applied to the handlebars, which meant that the Gilera had to be banked over far earlier than my Norton. Also, the frames were very variable and certainly needed their steering dampers.’

Read also found that Duke was prone to criticizing his riding ability: ‘He was watching me in practice at Stavelot and tore me off afterwards for my cornering and gearchanging. Doing this in public in the pits was not particularly confidence boosting.’ All in all, the ambitious Read was increasingly frustrated, believing that Gilera’s effort was hopelessly underfinanced and lacked a presiding mechanical genius such as MV enjoyed in Arturo Magni. Nevertheless, he came home second at Spa, behind Hailwood, with whom he now shared the championship lead. At this stage, Minter returned to the fold, testing the bike at Monza. He broke the lap record unofficially, but then lost the front forks when braking from 100 mph; a bolt had not been tightened properly and had worked loose. Uninjured, he was able to win his comeback race at Oulton Park, turning in a record lap. Hailwood emphasized his and the MV’s all too evident superiority at the Ulster GP, recording the first series of 100 mph laps of the Dundrod course to beat Hartle. Minter, upset by a further difference of opinion with Duke regarding faulty boat bookings, trailed home a distant third, dispirited as the bumpy circuit aggravated his already painful back. Before the race, Duke announced to the assembled press that he expected Hartle and Minter to challenge for the lead and that he hoped Read would perform respectably. This honest if unwisely expressed appraisal of his riders’ prospects stung Read into riding beyond the limit. He dug a footrest in at Leathemstown on the second lap and duly stepped off, hurting his back in the process. One telling statistic emerged from the flying kilometre trap at Dundrod; the MV clocked 143.5 mph, whereas the best Gilera, Minter’s, could summon no more than 138 mph.

Hailwood was simply unbeatable at Sachsenring, home of the East German GP, with victories in the 250 cc, 350 cc and 500 cc classes. Although Hartle came to grief, Minter salvaged second place in the Senior event. A solitary Gilera remained unscathed after the recent prangs; it was accorded to Hartle for the Finnish GP at Tampere, but gearbox problems jinxed his effort. Hailwood, needless to say, dominated the race.

The revised cylinder head which Passoni had designed in anticipation of the 1958 season was now pressed into service on Minter’s bike for the crucial Italian GP. It sported deeper finning to assist cooling and was slab-sided to reduce width. Unfortunately, its adoption necessitated time-consuming modifications to the carburettors, frame and tank, diverting attention from the other machines. Hartle’s competitive Gilera career came to an unscheduled conclusion when he hit the Monza tarmac at 130 mph during practice; he incurred only superficial injuries, but the bike was wrecked. In the race, the Gilera riders were humiliated by Hailwood and Venturi. Read pulled out when huge uncontrollable slides materialized; the nut attaching the gearchange linkage to the gearbox shaft was too tight to allow for expansion of the crankcase when the engine was warm, causing the pedal to stick in fourth gear. Minter realized he was on a loser when Venturi motored past him; badly-machined internals in the new gearbox and an oil leakage brought his challenge to an untimely end.

It was this unmitigated fiasco, on home territory, rather than the string of disappointments throughout the season, which incurred the intense displeasure of the Gilera factory management and sounded the death knell to Duke’s project. The squad did not travel for the Argentinian GP, which fell, inevitably, to Hailwood ahead of a host of local riders including, in third place, one Benedicto Caldarella. At season’s end, Hartle and Read were third and fourth in the title standings, ousted from runner-up spot by privateer Alan Shepherd on his Matchless. The team did, however, compete in the remaining home internationals. At Scarborough, Minter unceremoniously dropped his mount on loose gravel at Mere Hairpin and Read notched his solitary race victory on a Gilera. Having recorded a couple of successes at Brands, Minter was roundly beaten by Hailwood in the money spinning Race of the Year at Mallory. In October, Duke arranged for Hartle to test the bike with a leading-link front fork, designed by Ken Sprayson, at Monza.

The disillusioned factory staff were not convinced that Duke should run next year’s show and independently invited Hailwood, Venturi and new-sensation Giacomo Agostini to test the machine. Understandably, MV, Bianchi and Morini respectively would not release their stars and so a handful of promising riders were given a run-out, including Renzo Rossi of Bianchi, and Alberto Pagani and Gilberto Milani of Aermacchi, without justifying a contract. Duke was hoping to arrange an Australasian tour over the winter for either Hartle or Alan Shepherd, but he notified Minter that his services would no longer be required. Duke’s grandiose plans were brought to nought for, at the end of the year, Gilera’s grandson Massimo Lucchini, who had attempted to liaise between the English squad and the factory personnel, informed Duke that the machines would not be made available to him for 1964.

Derek Minter, Mike Hailwood, John Hartle